Our “branch” in Japan

Hiroshi Watanabe is owner of the Confiserie Bachmann in the Japanese town of Hiratsuka, a suburb of Tokyo. Thirty years ago, he attended the Richemont School in Lucerne with the aim of one day opening up a genuine Swiss patisserie in Japan. At the time, he was a pioneer. And of course he needed an appropriate name for his venture. He was taken with the pink company Bachmann and the city of lights itself. When he returned to Japan, he opened up his own patisserie that very much resembled a Bachmann branch.

Sweet Japan Awakens

Being a confectioner is simply fantastic, requiring creativity and the pursuit of flavors. How diverse, yet delicate our profession can be, we experienced once again in Japan. The attempt to explore new possibilities brought us many new ideas, joy of life, and became an essential part of our training as confectioners. In addition to our professional goals, we also enjoyed the special time in the Land of the Rising Sun. Especially when we slept on straw mats on the floor, took a sip of rice wine from a tiny bowl, reflected on the unusual dishes made of fish and vegetables, and experienced the perfection and strict order of traditional Japanese life.

In Japan, a clear distinction is made between European patisseries and traditional local shops. Japanese specialties have little in common with ours, are often heavy, and are usually made from bean paste. They are still very popular, especially among the older generation or in rural areas. However, in recent decades, it was European sweets that experienced a great boom, and this became our main focus.

Why did European patisserie come to Japan?

Due to the large number of American soldiers in Japan after World War II, the demand for bread and pastries was high, and soon the first bread factories were established. Cakes and patisseries in the European style followed. Anyone who began producing brioches, pâte à choux, and Black Forest cakes naturally also needed a European name for their shop. Only then did it appear credible and authentically European. It is therefore not surprising that countless well-known European patisserie names can be found in Japan today. Many of these businesses operate under a franchise agreement, are mere copies, or increasingly even a type of branch of the main business located in Europe. Whether Fauchon, Dalloyau, Peltier, etc. – where half a century ago there was nothing, today all of these renowned patisseries can be found in Japan.

Patisseries we worked in:

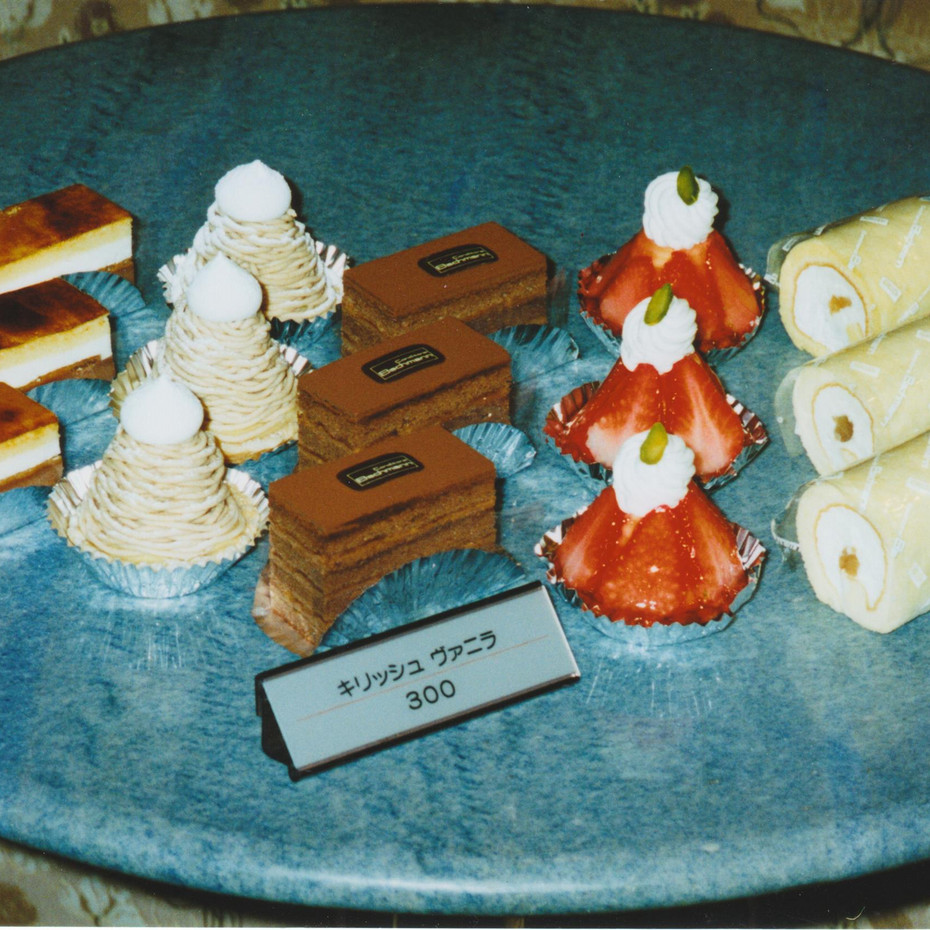

- Bachmann Patisserie in Hiratsuka

- Füßen Patisserie in Tokyo

- POIRE Patisserie in Osaka

From February to August we were on the “earthquake island” with the goal of tracing European specialties. We mainly worked in the production of the three following patisseries:

The Bachmann Patisserie in Hiratsuka looks, in its style, just like our family business in Lucerne. Hiratsuka is located about an hour by train south of Tokyo at the foot of Mt. Fuji. During rush hour, a train from Tokyo to Hiratsuka runs every 8 minutes. The route can be compared to Zurich–Lucerne. In April we moved to the 12-million metropolis Tokyo, where we worked in the production of Füßen Patisserie. In May and June, we were employed in the POIRE Patisserie in Osaka.

Afterwards, we embarked on a sweet journey of discovery and combed through the region from Osaka via Kobe, Himeji, Okayama, Hiroshima, Fukuoka, all the way to the volcanic city of Kagoshima, visiting patisseries along the way. From there we traveled back to Tokyo via Nagoya and Hamamatsu. In total, we visited 46 patisseries. The last days in Japan we spent at the Imperial Hotel, where we carved figures out of ice, and in Ginza (Tokyo) at the Pièce Montée Patisserie. This gave us the most beautiful and dreamlike conclusion.

From the bakery to the computer

During the day we worked in the patisseries, and in the evening after work, everything we had newly learned had to be entered into the computer. The smallest details were noted. Sometimes this lasted late into the night before starting again at six o’clock the next morning. It was a very intensive but equally fascinating time that shaped us. Of course, we were not spared the occasional minor earthquake.

The Japanese work systematically, meaning that work processes are always approached in the same way. Improvisation is not their strength. If a system fails, they quickly reach their limits. They work like machines, very precisely, always the same, and without questioning. Their creativity, especially with cakes and patisseries, was originally imported from Europe. But they have added something of their own and built upon it. It even happened that we tried Swiss specialties which actually tasted better to us in Japan than in our own country. Sad but true: the Japanese are clever, and in recent years they have refined the art of confectionery. Confectionery is alive, and to feel this was once again a joy for us.

In all patisseries, great importance was placed on proper attire. Hats were mandatory and had to reach down to the middle of the forehead. T-shirts were not allowed in the workplace, and the white work blouses were all printed with the colorful company logo. The long white fabric apron was always carefully tied around the waist with a special button. The differently colored scarf worn around the neck indicated the rank in the bakery, often based on the number of years worked in the business.

Work hygiene was comparable to ours. In general, it was considered very important, though there were differences from one business to another. Airlocks and overpressure systems that filtered the air were mostly found in larger companies. A bowl or piping bag was sprayed with alcohol before use, i.e., disinfected; knives were cleaned in boiling water before every cut.

Many work systems were exactly the same as in Europe — perfectly copied, so to speak. We even recognized useful procedures that had been lost in Europe over the years due to growing time pressure and rationalization. Among these were tools that our grandfathers and fathers once worked with. For example, to fill mousse into cups at exactly the same height, we found a thin wooden strip with nails hammered in at equal intervals. The strip was placed across a row of cups, and the mousse could then be filled up to the tip of the nail in each cup. This made it easy to fill all of them to the same level. Even better, the result would be exactly the same today, tomorrow, and even six months later. This is just one example of the many details we found so interesting. Moreover, Japanese confectioners also developed many improvements of their own, which can already serve as models for us today. The time has come for us to recognize that others have not been idle either.

We also noticed that the head of production was held in complete respect and there were no “ifs” or “buts.” Subordinates preferred to leave things unclear and tried to overlook them. If someone had a different opinion, they certainly kept it to themselves. People did not speak badly of others. The Japanese do not use bad words or outbursts.

The focus on quality in some businesses surprised us greatly and ranged from exemplary to exaggerated. For example, at Pièce Montée even the syrup was boiled with purchased mineral water, although the tap water in Tokyo is perfectly drinkable. Highest quality and freshness are of utmost importance to them. We were once again impressed by how fine the palates of the Asians are, particularly in the ice cream departments. Fruit was handled with great skill: the flesh of apples, mangos, papayas, and melons was carefully scooped out without damaging the skin, and the freshly made frozen ice cream was then refilled back into the original shell.

Especially in the preparation of biscuits, cakes, and sponges we were able to learn a great deal. It was astonishing how much was baked using steam. What amazed us even more was that roulade recipes made with milk were excellent in taste and interesting in their composition. When we watched them folding a mixture, it sometimes seemed as if they wanted to hypnotize it, so intently did they concentrate. The Japanese are tireless and take everything very seriously. One morning when we placed the cake slices lengthwise instead of crosswise in the box, we were immediately corrected. Individualists are not in demand in Japan. A person who clearly asserts and enforces their own convictions causes unease among the Japanese. The goal of human endeavor is not the free realization of the individual, but the harmonious integration of the individual and smooth cooperation. In Japan, respect is not given to those who stand out and distinguish themselves, but to those who adapt and fit in.

After visiting many patisseries, we considered the overall level to be high. What we somewhat underestimated, however, was the communication problem. Although English is the most common foreign language, it was rare to find someone who understood it even moderately well. Among professionals, French or even German was often more familiar. To appear completely “authentic,” recipe books were sometimes even written in German or French. Nevertheless, language remains the greatest barrier for Western newcomers.

A training system like the one our apprentices enjoy does not exist

There is unfortunately no practice-oriented school for newcomers to our trade in Japan. At this point, we would especially like to make apprentices aware of how valuable their training can be. Those who can afford it in Japan attend one of the well-run and strictly managed vocational schools in the four largest cities. The schools are very expensive and often last for two years. Afterwards, students enter working life. However, it takes years to pass through all departments in a business.

As it used to be with us, and in some cases still is, one must also put in their hours in Japan in order to secure a place in a good business. Many young Japanese are eager to learn and therefore accept extreme conditions. A six-day week and twelve-hour working days are quite normal in the good patisseries of Japan.

Anyone who wants to work at Pièce Montée in Tokyo, for example, will indeed learn the finest of the fine – but must work six days a week from 7:30 a.m. to 9:15 p.m. We would say: the higher the level, the longer the working hours. If you want to learn, you have to roll up your sleeves. At the Bachmann Patisserie in Hiratsuka, for example, work runs from 6:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Every Wednesday is a day off. Every other day, however, the confectioners and even the production manager have to help sell in the shop until 9:00 p.m. Anyone who wants to become a good confectioner in Japan must also be able to create beautiful packaging – complete with the appropriate bow. This is because the Japanese place great value on presentation. Vacations vary between 7–10 days per year, and public holidays are rare. The healthy diet probably gives the Japanese the strength for these tough conditions, but their private lives obviously suffer as a result.

The prices of patisseries and cakes vary. In Tokyo’s Ginza district, one pays top prices to satisfy the sweet craving. A single pastry at this prestigious location costs around CHF 8 to CHF 12. Paying CHF 2.50 for a praline is also common in Ginza. Outside the cities, however, prices are considerably lower.

Japan is another world

To make comparisons with our own is unrealistic. The longer we engaged with it, the more we became aware of the extreme differences in everyday life. Although we came from a distant country, with a different sense of humor, reacting differently and behaving in other ways, we were taken very seriously and treated with respect. At times, however, it was difficult to understand all the unwritten rules. Especially for Western visitors, it is the small, seemingly insignificant things one must be cautious with. There is no spontaneous or natural reaction to indicate what the boss, the saleswoman, or the colleague is really thinking or feeling. Every blink of the eye is rehearsed – the whole thing is a great masquerade.

We were often astonished by the different way of thinking, the correct behavior, and the respect they show each other. On the other hand, the many courtesies made life almost complicated again. How much importance is still placed on formalities, even among the younger generation, surprised us. For example, bowing at greetings is still fully intact. The younger or less superior person must bow once more in greeting. A matter of respect! Thus, one bows 4 to 8 times in succession, and what is important is that each time it is a little deeper. If there is great mutual respect, the bowing can go on for two minutes, and during it the conversation already begins.

Our professional curiosity was constantly awakened in the Land of Smiles. Our beautiful profession lives from the enthusiasm, even obsession, with new ideas. We were able to savor this to the fullest in a country where the confectioner did not even exist 50 years ago.

After six months we left Japan for Korea, where we were able to work for two weeks in the four largest artisan patisseries. The aim was to demonstrate some Swiss specialties. Our journey took us from Seoul, Taejon, and Ulsan to the southern city of Pusan. Today, there are some good bakery-patisseries in Korea. Overall, however, the level is still far from comparable to Japan. Afterwards, we continued on to Hong Kong and Singapore, where we mainly visited patisseries and hotels to gain further impressions of Asian craftsmanship.

Time allows one to mature, and we should think much more about how well we live and what we are striving for. We should value our health and, both professionally and privately, never stop striving to improve ourselves. Not necessarily perfection, but rather joy of life, zest for life, optimism, and honesty should be our goals.

Matthias und Raphael Bachmann